Fairy Faith

EPISODES: INTRODUCTION | The Egryn Lights | The Welsh Roswell | The Pembrokeshire Wave | Pentyrch and Smilog Wood | UFolk | Wee Folk Pt 1

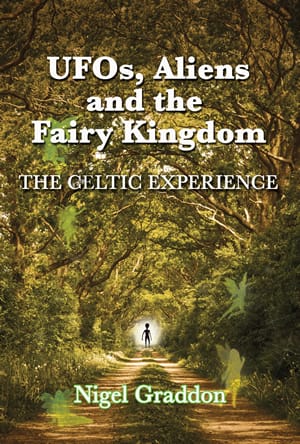

Episode 6 of UFOs, Aliens and the Fairy Kingdom by Nigel Graddon.

To know human life one must go deep beneath its sunny exterior; and to know that summer-sea which is the Fairy Faith one must put on a suit of armour and dive beneath its waves and behold the rare corals and moving sea-palms and all the brilliant creatures who move in and out among those corals and sea-palms, and the horrible and awful creatures too, creatures which would devour the man were his armour not of steel—for they all mingle together in the depths of that sea… hidden from our view as we sail over the surface of its sun-lit waters only.

—Walter Evans-Wentz

We have seen that the large number of documented sightings of UFOs and their observed occupants has facilitated efforts to arrive at a formalised approach to the physical classification of certain elements of the ufonaut community, principally the grey types which scientists believe are androids manufactured by unknown beings of high intelligence.

In the last lines of the previous chapter, we have also seen that American defence officials have arrived at the extraordinary conclusion that the point of origin of the NHE UFO phenomenon is connected with manifestations of “faerie” folk. What cannot be said is that humankind possesses any degree of empirical knowledge concerning the forms, physiologies and motivations of the intradimensional makers of the UFO occupants seen from time to time in our skies.

When lifeforms not associated with the appearance of “flying saucers” emerge as if through a door in a hillside we, the observers, become components in a living fairy tale whose principal characters may adopt a bewildering and, at times, a terrifying morphology. This is not to say that there is an absence of classification data regarding types or descriptions for the genre, but by virtue of its mythological and folklorist nature the taxonomy is understandably less well populated.

The scriptures tell many stories of encounters with unworldly beings. Ezekiel described angels in human form called cherubim (Hebrew: “full of knowledge”):

…their appearance like burning coals of fire, and the appearance of lamps: it went up and down among the living creatures: the fire was bright, and out of the fire went forth lightning.

Enoch dreamed of:

…two men, very tall, such as I have never seen on earth. And their faces shone like the sun, and their eyes were like burning lamps.

These men took Enoch into the sky and conducted him on a tour of “seven heavens.” Daniel saw “wheels as burning fire” and encountered an entity that came down from a “throne” in the sky, dressed in a white robe with a gold belt, and had a luminous face with two bright glowing eyes.

Daniel’s vision of the wheels of fire

Ufologist John Keel read the Bible many times. He concluded that in light of present-day knowledge about UFOs, many Biblical accounts take on new meanings. In olden times those who saw strange objects in the sky sought help from their priest who said God was showing us signs. Nowadays, we ask questions of the airforce, astronomers and quantum physicists.

The civilizations of Greece, Rome, Egypt, China and India believed implicitly in satyrs, sprites, and goblins. They peopled the sea with mermaids, the rivers and fountains with nymphs, the air with fairies, the household and its warming fire with the gods Lares and Penates, and the earth with fauns, dryads, and hamadryads. These inhabitants of nature’s finer realms were held in high esteem and were propitiated with appropriate offerings. Occasionally, as the result of atmospheric conditions or the devotee’s gift of second sight, the nature spirits became visible.

The Hebrews called these beings between Angels and Man Sadaim; the Greeks, transposing the letters and adding a syllable called them Daimonas. The Philosophers believed them to be the Aerial Race that ruled over the Elements.

The founder of Christian monasticism, the Egyptian St. Anthony, met a tiny being in the desert. It was a “manikin with hoofed snout, horned forehead, and extremities like goat’s feet.” On being asked what it was, the manikin said,

I am a mortal being… that the Gentiles… worship under the names of Fauns, Satyrs and Incubi. We [my tribe] entreat the favour of your Lord, and ours, who… came once to save the world, and whose sound has gone forth in all the earth.

The peasants of mediaeval rural France believed in the existence of a strange country called Magonia. There, the Magonians rode about in “cloud ships” and frequently made sorties from their realm to steal the peasants’ crops and livestock. One of these Magonian ships was recorded by Agobard, Archbishop of Lyons, to have fallen from the sky around 840 ce: ‘I saw…four persons in bonds: three men and a woman who… had fallen from these same ships.’ Angry farmers stoned all four to death.

There is no logical reason why one should deny the existence of things that cannot be seen with the naked eye. Belief in such matters is wholly relative to the degree of trust we place upon our instincts. Many townsfolk may never see a kingfisher or a dormouse in their lives but that does not make the bird or mammal any less real. On a more abstract level, we cannot see the wind but we are reminded of its presence each and every day. Why cannot the same principles of faith and intuition sustain a belief in the Wee Folk?

Walter Evans-Wentz made an outstanding contribution to fairy lore. An American anthropologist and writer, he is most famously known for publishing an early English translation of The Tibetan Book of the Dead. Born in Trenton, New Jersey, from a German father and an Irish mother, Evans-Wentz read Madame H.P. Blavatsky’s Isis Unveiled and The Secret Doctrine in his teenage years and went on to develop his interests in Theosophy and the occult. At Stanford University he read religion, philosophy and history, moving to Jesus College Oxford in 1907 to study for his doctorate in Celtic mythology and folklore. For these studies Evans-Wentz (pictured below) undertook very considerable fieldwork, collecting fairy folklore in Wales, Scotland, Ireland, Cornwall, Brittany and the Isle of Man. He was not alone among contemporary creative figures in believing in the reality of the fairy faith. W.B. Yeats wrote to Evans-Wentz saying that “I am certain that the (Fairy Folk Kingdom) exists and will some day be studied as it was by Kirk.”

In Evans-Wentz’s day the growing influence of psychology and the public’s fascination with psychic phenomena forced researchers to address the possibility of invisible intelligences and entities able to interact with and influence man. This new line of thinking was known as the Psychological Theory of the existence of fairy-folk. Evans-Wentz was a leading proponent, believing that a greater age is rapidly approaching when all the ancient mysteries will be carefully studied and the Celtic mythologies in particular will be held in very high esteem.

Evans-Wentz’s understanding was that the heaven world of the Celts is not to be found in planetary space but here on Earth. He said that the businessman’s rational mind denies him the possibility of seeing fairies because their whole world is subconscious and materially orientated, completely closed to nature’s energies and influences. In contradistinction, the Celtic mystic believed that the universe comprises two interpenetrating parts: the visible world and the invisible realm of the fairies, which are intelligent beings that reside in the Otherworld and occupy all orders of society and hierarchy. Evans-Wentz’s intensive research into the Fairy Faith[1] led him to conclude that there had never been a time in human history when there was not a belief in an unseen world peopled by invisible beings. Ancient man called them gods, genii, shades and daemons (the latter not regarded as evil but as allies of man); Christians spoke of angels, saints, souls and (evil) demons; Celts spoke of gods and fairies of many kinds.

Evans-Wentz accepted as fact that lying deep within the human psyche is a powerful atavistic recognition that separate races of beings inhabit an invisible world or worlds contiguous with our own. What we see in myths, legends and fairytales is a reflection of man’s continuing struggle to explain in human terms this unseen world, its inhabitants and laws, and mankind’s relation to it.

Native Americans believe that humans are but one race inhabiting the earth. Others held in reverence by them include the Standing People (the trees), the Stone People (the rocks), the Four-Legged People (the animals), the Plant People (all that grows), the Feathered People (the birds), and the Crawling People (insects).

A painted ‘elf door’ in Selfoss, Iceland – photo by Bob Strong/Corbis

The belief of the Icelandic people in fairies is so deeply engrained in their culture that its government introduced in 1990 an Act under which conservation projects may only proceed if they are not prejudicial to the wellbeing and security of the country’s álagablettir—enchanted spots—and their elven inhabitants. The Icelandic Road and Coastal Administration is so used to dealing with enquiries it now has a standard response to journalists:

It cannot be denied that belief in the supernatural is occasionally the reason for local concerns and these opinions are taken into account just as anybody else’s would be.

In the past, the Administration adds, “issues have been settled by delaying construction projects so that the elves can, at a certain point, move on.” By any measure of what constitutes modern day progressive governmental thinking, the Icelanders are way out in front in making and vigorously enforcing this remarkable piece of legislation.

Evans-Wentz spoke with an Irish mystic about his knowledge of the fairy folk. He said that there are three great worlds that we can see while we are still in the body: the earth-world, mid-world and heaven-world. He explained that Ireland’s Sidhe (its fairy folk) are divided into two great classes: those that are shining and occupy the mid-world, and those that are opalescent through whose bodies runs a radiant, electrical fire, their heads aflame with a wing-like auras. This class resides in the heaven-world and its inhabitants are rarely seen. Its members hold the positions of great chiefs or princes among the magical tribes of Dana.

The mystic explained that among the shining orders there does not seem to be any individualized life; thus, if one raises his hands all raise their hands, and if one drinks from a fountain all do. It was the mystic’s understanding that the shining beings seem to move and to have their real existence in a being higher than themselves, to which they are a kind of body. They are also capable of creating new elemental forms by breathing forth beings out of themselves.

Isle of Man resident John Davis told Evans-Wentz that he believed fairies are the lost souls of those who died in Noah’s Flood, adding his conviction that there are as many kinds of fairies as there are populations here on Earth.

Nineteenth century folklorist Michael Denham listed 198 different types of fairies and associated forms in his two-volume work.[2] Here is an extract:

What a happiness this must have been… when the whole earth was overrun with ghosts, boggles, bloody-bones, spirits, demons, ignis fatui, brownies, bugbears, black dogs, spectres, shellycoats, scarecrows, witches, wizards, barguests, Robin-Goodfellows, hags, night-bats, scrags, breaknecks, fantasms, hobgoblins, hobhoulards, boggy-boes, dobbies, hobthrusts, fetches, kelpies, mum-pokers, Jemmy-burties, satyrs, pans, fauns, tritons, centaurs, calcars, imps, spoorns, men-in-the-oak, hell-wains, fire-drakes, kit-a-can-sticks, Tom-tumblers, melch-dicks, larrs, kitty-witches, hobby-lanthorns, Dick-a-Tuesdays, Elf-fires, Gyl-burnt-tails, knockers, elves, raw-heads, Meg-with-the-wads, old-shocks, ouphs, pad-fooits, pictrees, giants, dwarfs, tutgots, tantarrabobs...

To this list, Thomas Keightley from his studies added:

Bull-beggars, Jack-wi’-the-Lanthorn, Calcars, Coujurors, the Spoorn, the Irish Cluricaun, the Mare, the Highlands Urisk, the Puckle, the hairy brownie-like Phynnodderee of the Isle of Man, and the mischievous English Portune. Keightley described the latter as no more than half an inch tall with the appearance of a very old man in a patched coat. For sport it will tease horsemen by invisibly taking the reins and leading the horse into a bog before running off laughing.[3]

If one uses Katherine Biggs’ invaluable dictionary[4] as a starting point and extrapolates accordingly, the figures increase exponentially. Briggs, focusing exclusively on Britain, listed hundreds of different fairy types, sub-types and variations. She was deterred from expanding the scope of her work to include Europe’s fairies owing to the many additional years of enormous effort required to meet the task. Europe has scores more distinct ethnic groupings than Britain, while globally some estimate them to exceed twenty thousand.

If we stand back and consider the numbers, we may conclude that in terms of comparable scope and scale, the fairies’ invisible home may be visualised as a world just like our own, with at least as many residents of all shapes, sizes, temperament, and social and cultural variations.

Evans-Wentz believed that people who inhabit the Celtic regions are more in tune with their subconscious selves and so better equipped psychically to feel and perceive invisible influences. He believed that through this enhanced faculty the Celts enjoy an innate ability to respond to nature’s rhythms and, correspondingly, can feel the essence of this Otherworld more keenly than most. Being part Celtic on his mother’s side, Evans-Wentz firmly believed in the existence of invisible life forms, describing them as being as much a part of nature as visible life in this world. Consequently, he decried the use of the term “supernatural” to describe these beings, on the basis that, logically, nothing in existence can be supernatural.

What precisely is a fairy? In seeking to answer this question it is important to understand that the word “fairy” per se is no more than a relatively late etymological construct. It does not appear prior to the mediaeval period and its initial use referred specifically to mortal women with mooted magical powers (as personified, for example, by the Arthurian figure of Morgan le Fay; in fact, fairy can also mean a spell for a fay). “Fai” is derived from the Italian “fatae,” the otherworldly women who visit a child at birth to determine its future as in the mythological role of the Three Fates. “Fai” was extended into “fai-erie” then conjoined as “faerie” to indicate a state of enchantment, while the French “fée” described a woman skilled in the healing arts and in the corresponding magical use of herbs, potions and minerals. It is a dreadful stain on humanity that in medieval times a great number of village “fees”, midwives, herbalists, healers and the like, were sent to the stake as “witches” in huge numbers (estimated as up to 600,000 since 1200).

Eventually, the use of the word “fairy” to refer to unseen beings became a distinctly English development. Folklorists trace this to a conflation of the ancient German tradition of elves and dwarfs (huldra or hudufólk—hidden people) with Celtic influences. In turn, this led to the formulation of an image of fairy folk as a largely diminutive race, in contradiction to folklore in which fairies are depicted in every shape and size. By the time of the Victorians and their love of twee children’s stories, fairies were being portrayed as mischievous but essentially good-natured, tiny winged creatures.

This contrasts sharply with James VI of Scotland’s 1597 description of fairies in his “Daemonologie” as demonic entities that consort with and carry off individuals. William Shakespeare is believed to have drawn inspiration from James’s book in creating the three witches for Macbeth, thus perpetuating the stereotypical attitude of the day that wise women were supernatural figures to be feared and punished.

Seen in this perspective, one can readily appreciate that an objective student of “fairies” must face a stiff reality check. They must accept that there is neither consensus on how a distinctly human mediaeval village healer became transmogrified over time into a winged Wendy figure, nor on the word’s relevance and meaning in the twenty-first century. This internal dialogue might conclude that seeking to apply a label to something of such flimsy provenance is to neglect far wider possibilities of discovery and learning.

Armed with fresh insight, the student may come to understand that if he continues striding down an increasingly narrow “fairy” path he will become ill-equipped to deal with other creatures that might jump out from the bushes, like gnomes and goblins and other truly bizarre entities such as the It, the Boneless and that weird hotchpotch of present day tricksters collectively termed Road Ghosts. This is our intrepid investigator’s Eureka moment. In a flash, he sees that what he is actually seeking to understand are, purely and simply, non-human entities that defy categorisation and description.

Seventeenth century Scottish minister Robert Kirk became a much-lauded authority on the fairy folk. Kirk stands apart among folklorists. Not only did he provide stories of unparalleled insight as if from personal experience but he also was the subject of a fairy story. Many in his day believed that Kirk did, in fact, commune with fairies and that, finally, they carried him away into their underground world.

Born in Aberfoyle, Scotland, in 1644 Robert was the seventh and youngest son of James Kirk, minister at Aberfoyle in the county of Perthshire. After a course of study at St Andrews, Kirk received his master’s degree in theology at Edinburgh in 1661, becoming minister of Balquhidder three years later and of Aberfoyle on his father’s death in 1685. In 1670 he married Isobel, daughter of Sir Colin Campbell of Mochaster. From this union came a son, Colin. When Isobel died on Christmas Day 1680 Kirk cut out an epithet with his own hands. Later he married Margaret, daughter of Campbell of Fordy, who after her husband’s death in 1692 bore a second son, Robert, later minister at Dornoch in Sutherlandshire.

Robert Kirk Sr. was a renowned Gaelic scholar. Among his chief accomplishments were the first metrical translation of the psalms into Gaelic and his participation in the printing of a Gaelic Bible (An Biobla Naomhtha), a project funded by Robert Boyle of the Royal Society. Boyle was fascinated by Kirk’s gifts as a man of the Second Sight and made efforts to pursue enquiries of his own.

Kirk is universally known for his Secret Commonwealth,[5] a treatise on fairy folklore, witchcraft, ghosts and second sight, written in 1692 but not printed until 1815. In its Foreward, Kirk described the work as “An Essay of the nature and actions of the subterranean (and, for the most part) invisible people, heretofore going under the name of ELVES, FAUNES, and Fairies, or the like, among the low-country Scots, as they are described by those who have the second sight; and now, to occasion further enquiry, collected and compared, by a circumspect inquirer residing among the Scottish-Irish in Scotland.” His study is objective and impartial but its overall empathetic tone indicates that he believed absolutely in the existence of fairy-folk.

Transcending the ignorant belief of the time that fairies were witches or midwives, Kirk said that fairies are of a middle nature between man and angels, varying in size, powers, life span and moral behaviour. Mentally and physically (Kirk was reputed to have the gift of second sight) he saw a canvas populated by spirit forms that occupy invisible realms between this universe and the heavenly spheres.

Kirk wrote that the good people, the sleagh maith, are of a middle nature between man and angel as were daemons of old. He described them as intelligent studious spirits with light, astral changeable bodies akin to a condensed cloud. Some, he said, have bodies so spongy, thin and pure that they feed only by ingesting fine spirituous liquors that pierce like pure air and oil. Others, he said, feed more grossly on foison (harvest produce), including corn, which fairies steal away, partly invisibly and partly preying on the grain in the manner of crows and mice. (This physiological description is closely analogous with that of category EBE Type 1 NHE entities, which feed on plant material and use photosynthesis to convert the food to energy.)

In 1705 Kirk’s contemporary, John Beaumont, published his Treatise of Spirits, describing encounters with fairies. He once saw them dancing in a ring. They were 3-feet tall with brown complexions, wore black, loose, netting-style gowns tied with a black sash, and a golden garment with a light striking through it. Adorning their heads were white linen caps with lace on them covered with a black network hood. Beaumont asked them what they were. They said that they were an order of creatures, superior to mankind and could influence our thoughts and that their habitation was in the air.

Kirk said that fairies are distributed in tribes and orders and, like humans, have children, nurses, marriages, deaths and burials. They live far, far longer than humans before they vanish into the element from which they are composed. He stated that fairy-folk are not subject to human ailments but dwindle and decay after a certain period. He suggested that their sad disposition is a reflection of their uncertainty about what will become of them on the Day of Judgement. Kirk remarked that fairies’ bodies are fashioned from congealed air and are sometimes carried aloft; otherwise, they grovel in different shapes and enter their dwellings through any cranny or cleft in the earth, it being full of cavities and cells. Their dwellings are lit by continual lamps and fires in the Rosicrucian style with no apparent fuel to sustain them. In them food is served by pleasant children who act like enchanted puppets. The fairies can sometimes be heard baking bread and striking hammers. Kirk described fairy speech as “whistling, clear, not rough.” In their relaxation periods, fairies prefer books on arcane subjects.

Loath to stay in one place for too long, fairies change lodgings every quarter. They love to travel abroad, their chameleon-like bodies swimming in the air near the earth with bags and baggage. It is at these times that those with the second sight have encounters with fairies. Those with the sight may only see a fairy between two blinks of an eye. Kirk is describing here the “trooping fairies,” the gregarious type that live in communal groups, usually under mounds or hills. Their social structure closely imitates that of humans, ordered according to rank with aristocrats (the kings, knights, ladies and royal courts of the Heroic Fairies) at the top of the chain, followed by the gentlemen and then the rustic, peasant folk. Troopers enjoy undertaking rades, solemn processions on foot or on horseback; and the Heroics have a particular fondness for hunts, battles, sporting games, feasts and balls. Processions of trooper fairies may be seen on the night of a full moon at a spot where four roads cross.

In Gaeldom, the regions in which Gaelic is spoken (Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man), the invisible race is known as the “Shee,” (more precisely, the Sluagh Sidhe, people of the mounds), the Gentry, or just the folk. The Irish call the world of the Shee the Middle Kingdom, its inhabitants for the most part recognisably human-like, just as Tolkien portrayed the majority of folk in Middle Earth.

The Gentry were described to Evans-Wentz as a folk far superior to us. In Irish mythography they are a unique race between humankind and the spirit world, comprising a military-aristocratic class, noble in appearance. They range in height and build from child-size to unusually tall, fully grown men and women. They speak in a sweet, silvery voice and play the most beautiful music.

Kirk remarked that when men and women meet a fairy it is more likely to be one of the Gentry. He said that many among this class have human ancestry, some even being half-human. Though they may look human the Gentry have magic aplenty. They can take many forms, make things seem other than they are and time stretch or contract.

A witness told Evans-Wentz of a member of the Gentry that once appeared to him. He was stoutly built and appeared to be only four feet tall but told the witness:

I am bigger than I appear to you now. We can make the old young, the big small, the small big.” Compare this statement with an exchange between a witness and a UFO occupant. The occupant told him he would see its form only as he wanted to see it. If I wanted to see the being in the semblance of a duck, said the witness, it would look like a duck. If I wanted it to look like a monster, it would look like a monster.[6]

Humans with second sight see fairies at banquets and burials. The wee folk have even been seen to carry a coffin to the graveside. On these occasions some claim to have seen a double-man or the shape of a man occupying two places at once. Men call this double the reflex-man or co-walker, in every atom of detail identical to the man it replicates.

The Scottish fairies’ graveside tradition is echoed in Welsh folklore, which describes instances where fairies have been seen in churches participating in phantom funerals called “toeli.” In Wales the will-o’-the-wisp lights are known as canwyll corfe—corpse candles: harbingers of pending death.

Kirk contrasted the trooping fairies with the solitary kind, the “Unseelie Court,” populated, it is said, by the unblessed dead and those expelled from the Seelie Court. Their appearance is likened to a great black cloud that passes ominously overhead in the breeze at night. For the most part, the Unseelie Court keep their own company but will on occasion come together to have meetings or hold fairs. On the whole, the solitary fairies are far less kindly disposed to humans but according to Kirk only a handful are truly inimical.

Kirk enjoyed visiting at night a fairy knowe (knoll) beside the manse, his minister’s residence. He would roam around in his nightgown before turning in. On 14 May 1692 he was found lying unconscious on the knowe (in Scottish Gaelic sith bhruaich and in Irish Mullach na Sidhe). He died without regaining consciousness and was buried in the Aberfoyle churchyard. His grave bears the inscription, Robertus Kirk, A.M., Linguæ Hiberniæ Lumen.

A fairy knoll?

There are many who believe that what lies in the tomb are ashes, stones or even a fairy-made doppelganger. Many of Kirk’s parishioners held that he had broken the taboo against spying on the fairies and as a punishment the body was replaced by a stock, a rough resemblance of a person fashioned in wood by the fairies. They impregnate the stock with “Glamour” to imbue it with a temporary appearance of life, which soon fades. Often the fairy changeling would be a baby (known in Scotland as the “wee diel”), but occasionally the fairies would take an older person they were glad to be rid of. Others said that Kirk “went to his own herd” and was serving as “Chaplain to the Fairy Queen.” Some even said that Kirk had been a changeling since birth, placed by the fairies on earth to serve as their ambassador from the Secret Commonwealth to acquaint lesser mortals with their ways and customs.

It is claimed that after Robert Kirk’s funeral he appeared to his relative, Grahame of Duchray, and said that he was not dead but had been carried off under the fairy knowe at Aberfoyle. He said that he had one chance of escape. He explained to Grahame that his child had just been born. He said that if Grahame’s child was christened in the manse, then he could exert his power beyond the confines of the fairy knowe and appear in the church. Grahame must at that moment draw his dirk and throw it over his apparition. The fairies, unable to counter the magical power of iron, would then have no choice but to disenchant him and set him free. On the day, Grahame was so transfixed by the sight of Kirk’s appearance in the church that he failed to draw his dirk. Kirk’s image then disappeared and his imprisonment continued. However, legend had it that a second chance would one day become available. During the Second World War an officer’s wife, a tenant of Aberfoyle Manse, was expecting a child. She was told that if during the christening someone stuck a dirk into Kirk’s favourite armchair his soul would be released. This act of mercy never took place and Kirk’s fate was sealed forever.

In the daunting task of defining fairies, folklorists often defer to Kirk’s categorisation. In John Gregorson Campbell’s acclaimed work[7] he took up Kirk’s line of thinking in saying that fairies are counterparts of mankind. Although the concept of dimensions that interconnect with Earth was not a hot topic of conversation in the late Victorian era, Campbell’s statement indicates that, presciently, he visualised parallel worlds inhabited by beings perhaps much like ourselves but with greater variation, type and appearance.

Welsh myth, too, proceeds along similar lines in suggesting that fairies are a real race of invisible or spiritual human-like beings, rarely seen, who inhabit a world of their own. The ancient Celts went further, believing that fairies could be embodied as members of the human race, echoing, for example, our present-day concept of the “walk-in.”

A belief in the existence of a class of beings, not human but belonging to the world of man, seems to be universal.

—Professor Reidar Thoralf Christiansen

Shakespeare was the first writer to describe fairies as picturesque descendants of nature spirits equipped with tiny wings. The true fairy tradition, however, refers to fairies that look very much like humans, only rather smaller, which makes it easier for them to infiltrate our communities unnoticed. John Michell[8] observed that this characteristic of fairies has engendered the fear that persists to the present day that there are those among us who are decidedly not human.

According to Janet Bord,[9] one of the traditional tests of the fairy nature is the ability for fairies and humans to intermarry and produce children. Bord explains that the “Little People” were so-called because, as far as one could judge, they were naturally formed people small in stature, whose distinct mode of dress set them apart from normal human convention and made them conspicuous.

Others hold that fairies are descended from a primitive earth dwelling race that was driven into hiding in the far distant past by invaders. While others believe that fairies are variously fallen angels, the souls of the dead, the descendants of the Greek and Hindu gods, the elementals of the mediaeval mystics, astral or elemental spirits, once mortal beings of flesh and blood before withdrawing into the Otherworld, or vestiges of pre-Christian religious teachings.

Evans-Wentz echoed this last opinion, suggesting that a belief in fairies has the same origin as all religions and mythologies. His extensive research revealed that fairy faith grew out of a pre-Celtic belief, probably among the more learned members of society, and paralleled the sophisticated Eastern systems of metaphysical sciences and esoteric philosophies.

Katherine Briggs found merit in all of these ideas, including Jung’s psychological theory but counselled against accepting one over another. She wrote, “On the whole we may say that it is unwise to commit oneself blindfold to any solitary theory of the origins of fairy belief, but that it is most probable that these are all strands in a tightly twisted cord.”

Folklorists and mythographers tend to agree that fairy folk find humans objectionable and dislike the use of the term “fairy,” which is why people tend to speak of them in placatory terms, using phrases like the Good Neighbours, the Wee Folk, the Gentry, the People of Peace, the Seelie Court, and Scotland’s “Grey Neighbours” (grey-clad goblins) so as not to get on their wrong side (because wherever we are they can always hear what we are saying).

Evans-Wentz described the fairies’ homeworld as a subterranean region invisible to humans except under special circumstance. Through secret passages and beneath mountains, raths, moats and dolmens, the Otherworld was once inhabited by the Partholon, the megalith builders of ancient Ireland. They were succeeded by the aristocratic and humanesque Tuatha dé Dannan who retired long ago after their defeat by the Sons of Mil into Ireland’s emerald hills together with the leprechauns, pixies, dwarfs and knockers (miners) of the fairy folk.

The Tuatha dé Dannan were the tall, beautiful Good People (Daoine Maithe), a highly cultured and refined race much like ourselves, who lived in the hills, married, bore children, toiled and feasted. They were extremely gifted in the fields of architecture, science, mathematics and engineering. They exercised command over the power of sound to lift and move massive weights. Over time, the Dannan, born from the “waters of heaven or space,” a representation of the goddess Anu (later Christianised as Brigit), became known as the fairy folk (later the Sidhe of folklore). In the Mabinogian Don means “the wizard children.” The enemies of the Dannan, the Fomorians, were children of the goddess Domnu, meaning an abyss or deep sea. Legend speaks of the Fomorians as a race of hideous giants (the Nefilim). In a description mindful of a Tolkien tale, the Fomorians were defeated on the Plain of Towers by a cataclysmic Flood generated by the Dagda Mor.

Anu’s wizard children include those that make fairytale witches appear sweet and tender. Black Annis is a cannibal hag with a blue face, long white teeth and iron claws. She lives in a cave in Leicestershire that she dug out with her own nails. Her blue-faced sister hag in the Highlands is Cailleach Bheur. Personifying winter, Cailleach Bheur is an analog of the Greek goddess Artemis.

Irish manuscripts refer to the Celts’ Otherworld as Hy-Brasil, a land once situated in the midst of the western ocean as though it were old Atlantis or its double. The Piri Reis map locates the island of Hy-Brasil 200 miles west of Ireland. Myth has it that Hy-Brasil appears to human sight every seven years. In 1908 at the beginning of Evan-Wentz’s Celtic odyssey Hy Brasil was seen by too many people for its existence to be dismissed as fantasy. Hy-Brasil’s ruler is Manannan Mac Lir, the Son of the Sea, foster father of Lugh, God of Light. He ferried the dying Arthur to Avalon. Manannan Mac Lir travels his domain in a magic chariot (so very reminiscent of UFO sightings). Fairy women would venture forth from this enchanted region, sprinkle mortal men with Glamour and entice them into their keeping.

Thousands of years after the reputed fall of fabled Atlantis Christians evolved their concept of Hell from this dark and fearful notion of the Celtic Otherworld. To those who perceived the Otherworld as a place of joy and happiness it was known variously as Tír Na nÓg, Land of Youth; Tir-Innambeoi, Land of the Living; Tir Tairngire, Land of Promise; Mag Mar, the Great Plain; and Mag Mell, The Happy Plain. To the ancient Greeks, it was the Elysian Fields. Intelligent and perceptive observers recognised that Tír Na nÓg interpenetrates our earth. They understood that the Otherworld is a composite term that encompasses all dimensions, which interlace the physical earth experience.

Evans-Wentz recounted the legend that to enter the Otherworld before the appointed hour requires that the seeker secures a “passport,” often a silver branch of the sacred apple-tree or simply just the apple. The apple branch sometimes produces music so soothing that mortals forget their plight when they are taken by the fairies to Tir N-aill. The Silver Bough of the Celts is synonymous with the Golden Bough and Golden Fleece of old. It is the Silver Cord that binds the astral body to its human host when journeying out of the body. The branch is the magic wand of the fairies, the caduceus of Hermes, and the staff with which Moses struck the rock to release pure water.

Across the Irish Sea in the Isle of Man fairies are known variously as the Little People (Mooinjer veggey), “Themselves,” “Little Boys” (Guillyn veggey) or “Little Fellas.” They are the men of the Middle World. On the Isle of Man’s Dalby Mountain, folk used to put their ears to the ground to hear the Sounds of Infinity (Sheean-ny-Feaynid), murmuring sounds that came from space, believed by Manx folk to be filled with invisible beings. This piece of folklore echoes Kirk’s Welsh story. He referred to the legend that Merlin enchanted the fairy folk to forge arms for Arthur and his Britons until their future return. Kirk said that ever since Merlin cast his spell one can stoop down on the rocks on Barry Island in the Vale of Glamorgan and hear the fairies at work: the striking of hammers, blowing of bellows, clashing of armour, and the filing of irons. The fairies are compelled to continue with their toil because as Merlin was killed in battle, he cannot return to loosen the knot that ties the Tylwyth Teg to their perpetual labours.

In England one form of house fairy is the charming “lob-lie-by-the-fire.” In Wales the same spirit is known as bwbach, brown and usually hairy. In Cornwall the Pobel Vean are known by names such as the Small People, Spriggans and Piskies, while the Buccas or Bockles are a deity not a fairy. The piskies are tricksters that delight in leading humans in circles and using the power of Glamour to seize them. In a Cornish account a brownie was:

a little old man, no more than 3-feet high covered with rags and his long hair hung over his shoulders like a bunch of rushes…having nothing of a chin or neck…but shoulders broad enow for a man twice his height. His naked arms out of all proportion, too squat for his long body, his splayed feet more like a quilkan’s (frog’s) than a man’s.

The dreaded Cyhyraeth

The fairies of Wales may be divided into five classes: the Ellyllon, or elves; the Coblynau, or mine fairies; the Bwbachod, or household fairies; the Gwragedd Annwn, or fairies of the lakes and streams; and the Gwyllion, or mountain fairies. The Ellyllon are the tiny elves that haunt the groves and valleys, and correspond with the English elves. The English word “elf” is probably derived from the Welsh el, a spirit, and elf, an element. Collectively, Wales’ invisible race is known as the Tylwyth Teg (the Fair Family). The Cyhyraeth is a ghastly figure seldom seen but can be heard groaning before multiple deaths at times of disaster. Accompanied by a corpse-light, it passes along the sea off the Glamorgan coast before a wreck occurs.

Welsh folklore offers a number of origins for the Tylwyth Teg. One has it that the first fairies were men and women of flesh and blood. Another portrays them as the souls of dead mortals, neither bad enough for hell nor good enough for heaven. They are doomed to dwell in the secret places of the earth until the Day of Judgement when they will be admitted into Paradise, an example of such being the Lady of the Lake who resides in Llyn y Fan Fach in the Brecon Beacons.

A story from Anglesey tells of a woman in the Holy Land who felt ashamed of having borne twenty children. So when Jesus visited her, she decided to hide half of her children away. Those ten children were never seen again for it was supposed that as a punishment from heaven for hiding what God had given her, she was deprived of her offspring, which went on to generate the race called fairies, the Tylwyth Teg.

Another name for the Tylwyth Teg is Bendith y Mamau (Mother’s Blessing, a term of endearment used to placate the fairies’ penchant for stealing away children). Numerous folklore tales highlight the Tylwyth Teg’s fatal admiration for handsome children, a compulsion which they must satisfy by stealing infants from their cradles and replacing them with a plentyn-newid (changeling). Consider this in the context of Albert Coe’s account:

In 1921, Albert Coe was told by his 340-year-old alien friend that, as early as 1904, the aliens replaced a hundred terrestrial babies and infiltrated their own. In the base of each baby’s brain was this little thing that recorded everything that that baby saw or did, from the time they put it there… No one ever knew it was a switch. Subsequently, as adults, the aliens became active in every major nation on Earth. Their main concern: that we were on the verge of discovering secrets of the atom, which could have disastrous consequences for our planet.[10]

Else Arnhem’s photographs of a fairy, taken in Germany, summer 1927

(Mary Evans Picture Library)

The fées of Upper Brittany are young and beautiful while others have teeth as long as human hands, their backs covered with mussels and seaweed indicating their great age. While the Breton lutins are in the same class of fairy as the farfadets in Poitou, the pixies of Cornwall, the English Robin Goodfellow and the brownies of Scotland.

The swamp area at Wollaton in Nottinghamshire where in 1979 six children saw around sixty little gnome-like figures at play

[1] Evans-Wentz, W., The Fairy Faith in Celtic Countries, London, New York, H. Frowde, 1911

[2] Denham, M., The Denham Tracts, The Folklore Society, London, 1895

[3] Keightley, T., Fairy Mythology, vol. 2, VAMzzz Publishing, Amsterdam, 2015

[4] Briggs, K., A Dictionary of Fairies, London. Penguin Books, 1977

[5] Secret Commonwealth OR, a Ttreatise displaying the Chief Curiosities as they are in Use amone the Diverse People of Scotland to this Day; SINGULARITIES for the most Part peculiar to that nation, published after the author’s death in 1692

[6] Hind, C., UFOs—African Encounters, Gemini, Zimbabwe, 1982

[7] Campbell, J., The Gaelic Otherworld, James Maclehose and Sons, Glasgow, 1900

[8] Michell, J., The Flying Saucer Vision, Abacus, London, 1974

[9] Bord, J., Real Encounters with Little People, Michael O’Mara Books, London, 1997

[10] Good, T., Earth: An Alien Enterprise, Pegasus Books, London, 2013

EPISODES: INTRODUCTION | The Egryn Lights | The Welsh Roswell | | The Pembrokeshire Wave | Pentyrch and Smilog Wood | UFolk | Wee Folk Pt 1