Note and disclaimer: This article was generated by AI and edited by a human. If you're interested in this topic, you should rely on your own resources and research.

Summary

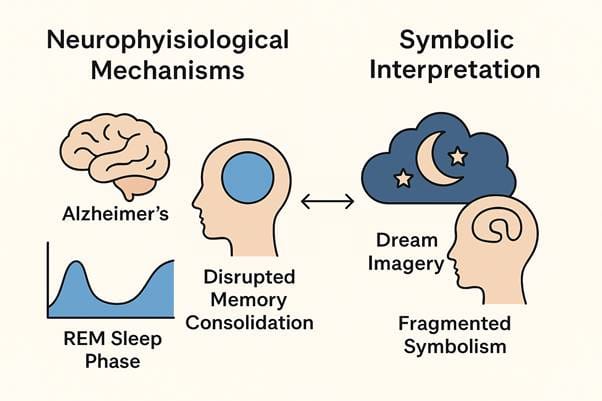

Modern neuroscience consistently finds that Alzheimer’s disease affects REM sleep—especially the vivid “dreaming” phase—and that this disruption correlates with cognitive decline, memory fragmentation, and emotional dysregulation. Studies indicate that decreased REM sleep duration and altered dream content can serve as early biomarkers for Alzheimer’s progression. While Jung’s analytical psychology predates current biomedical research, his view of dreams as symbolic processes integrating the unconscious can intersect with Alzheimer’s research when interpreting dream changes as signs of altered cognitive–emotional integration. Alzheimer’s dream changes—often fragmented, repetitive, or emotionally flat—mirror the neural degeneration seen in memory and emotion-related brain areas, including the hippocampus and amygdala.

Key Scholarly References

- Westerberg, C.E., et al. (2012). Sleep influences the severity of memory deficits in amnestic mild cognitive impairment: findings from REM sleep disruption. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 31(3), 585–596. DOI:10.3233/JAD-2012-120352

- REM sleep disruption correlates strongly with memory impairment in early Alzheimer’s stages.

- Liguori, C., et al. (2014). Altered sleep structure in Alzheimer's disease: Evidence from polysomnography and actigraphy. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 38(4), 969–975. DOI:10.3233/JAD-131186

- Reduced REM sleep percentage is a consistent Alzheimer’s marker.

- Mander, B.A., et al. (2016). Sleep: A novel mechanistic pathway, biomarker, and treatment target in the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease? Trends in Neurosciences, 39(8), 552–566. DOI:10.1016/j.tins.2016.05.002

- Explores how disrupted dreaming and slow-wave sleep impair memory consolidation.

- Pace-Schott, E.F., & Hobson, J.A. (2002). The neurobiology of sleep: genetics, cellular physiology, and subcortical networks. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 3(8), 591–605. DOI:10.1038/nrn895

- Discusses the role of cholinergic systems in REM sleep—these systems are degraded in Alzheimer’s.

- Miyata, S., et al. (2013). Dreaming in dementia: a study of dream recall in Alzheimer’s disease. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 28(5), 487–493. DOI:10.1002/gps.3842

- Alzheimer’s patients recall fewer and less vivid dreams, suggesting impaired REM-related memory encoding.

- Wamsley, E.J., & Stickgold, R. (2010). Dreaming and offline memory consolidation. Current Biology, 20(23), R1010–R1013. DOI:10.1016/j.cub.2010.10.045

- Links dream content with cognitive processing—framework relevant to Alzheimer’s dream changes.

- Jung, C.G. (1964). Man and His Symbols. London: Aldus Books.

- Jung emphasizes dream imagery as a communication from the unconscious, relevant to interpreting altered dream symbolism in Alzheimer’s.

- Jung, C.G. (1960). The Structure and Dynamics of the Psyche. Princeton University Press.

- Describes the compensatory and prospective functions of dreams—concepts that can frame the psychological meaning of altered dream patterns in neurodegeneration.

AI generated audio podcast

How Jung’s Perspective Connects to Alzheimer’s Dream Research

- Jung saw dreams as a bridge between conscious and unconscious material. Alzheimer’s-related dream alterations could be interpreted not just as a neurological symptom but as a transformation (or collapse) in this bridge.

- Symbolic fragmentation in Alzheimer’s dreams parallels cognitive fragmentation, suggesting a psychosomatic narrative that blends Jung’s symbolic lens with neurobiological data.

Jung’s Perspective: Dreams as Autonomous Reality

- Jung’s view: Dreams are autonomous psychic productions from the collective unconscious, not mere byproducts of neural noise.

- He saw dream reality as a psychological fact—an inner reality that, while not physically tangible, can have real causal effects on our behavior, creativity, and even somatic states.

- Jung often treated dream symbols as if they existed in their own "psychoid" layer—partly psychic, partly connected to material reality. This concept approaches what he and Wolfgang Pauli called the unus mundus, a unified reality where psyche and matter are aspects of the same underlying order.

Multi-Dimensional Theory and Dream Perception

- In speculative physics, “multi-dimensional” often refers to additional spatial or temporal dimensions beyond the familiar three of space + one of time.

- Some models (e.g., certain interpretations of M-theory, hyperspace cosmology) allow for consciousness—or information processing—occurring in higher dimensions.

- From a symbolic psychology standpoint, dreams could be interpreted as the mind’s way of mapping or projecting information from such dimensions into imagery we can consciously experience.

Quantum Physics and the “Reality” of Dreams

- In standard quantum mechanics, there’s no accepted mechanism for dreams to literally be perceptions of a parallel universe.

- However, there are speculative frameworks:

- Many-worlds interpretation (Everett): all possible outcomes exist in parallel “branches.” Dreams could, in theory, reflect imaginative recombinations of real branches, though this is purely hypothetical and untestable.

- Quantum consciousness theories (e.g., Penrose–Hameroff Orch-OR): suggest that microtubule quantum processes may influence conscious states, but these remain controversial and don’t establish direct “parallel reality” perception.

- Jung and Pauli’s correspondence explored synchronicity, where inner psychic events and outer physical events align meaningfully without causal connection—this is where “dream reality” could manifest physically, but only as meaningful coincidence, not material intrusion.

Objective Manifestations of Dreams Crossing into the Physical

While dreams themselves do not physically spill into waking space, there are measurable, objective ways they influence reality:

- Behavioral enactment

- REM Sleep Behavior Disorder: individuals physically act out dreams due to REM atonia failure. This is literal dream imagery causing physical actions.

- Physiological changes

- Heart rate, breathing patterns, hormonal fluctuations correspond with dream emotional content.

- Creative output

- Historically documented cases (Kekulé’s benzene ring, Mendeleev’s periodic table) where dream imagery inspired verifiable physical-world discoveries.

- Psychosomatic effects

- Repeated dream themes can influence stress levels, immune function, and other bodily states.

- Synchronicity events (Jung’s lens)

- Dream symbols appearing unexpectedly in waking life, interpreted as evidence of an underlying unifying principle.

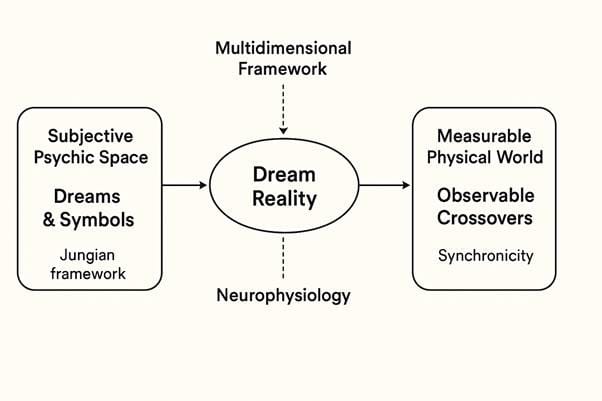

Integrated Model (Jung + Multidimensional Speculation + Physics)

- Inner psychic reality (Jung) → Exists in its own domain, with patterns shared across individuals via collective unconscious.

- Multidimensional space (speculative physics) → Could provide metaphorical or hypothetical scaffolding for how dream imagery transcends personal experience.

- Quantum/psychoid interface (Pauli & Jung) → Dreams and waking events might be linked by a deeper level of order (unus mundus) rather than direct causality.

- Observable crossovers → Behavioral enactment, creative problem solving, synchronicity patterns, and physiological shifts.

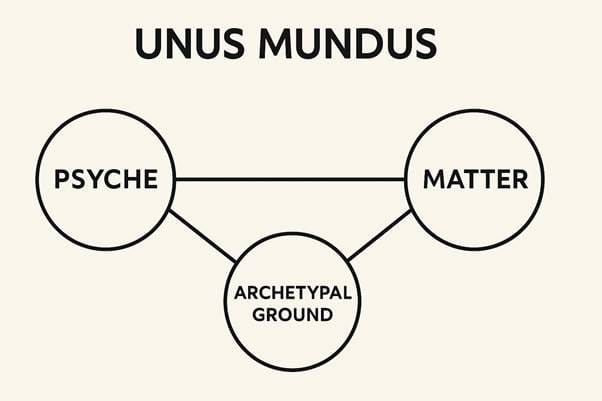

The unus mundus—Latin for “one world”—is a concept C.G. Jung and physicist Wolfgang Pauli explored in their intellectual collaboration during the 1930s–1950s.

At its core, it’s the idea that mind (psyche) and matter are not fundamentally separate, but are two expressions of the same underlying reality. Here’s a breakdown:

1. Philosophical Roots

- The idea isn’t entirely new—its heritage can be traced to medieval alchemy and even earlier to Neoplatonism and Heraclitus.

- Alchemists saw the transformation of matter and the transformation of the soul as parallel processes governed by the same cosmic principles.

- In the unus mundus view, the distinction between “inner” and “outer” is relative, not absolute.

2. Jung’s Interpretation

- For Jung, the unus mundus is the metaphysical ground from which both physical phenomena and psychic experiences arise.

- He saw archetypes—the deep structural patterns of the unconscious—as forms that can manifest in either psyche or matter.

- This gave a philosophical underpinning to synchronicity (meaningful coincidences): if psyche and matter share a common source, they can align without direct cause-and-effect.

3. Pauli’s Contribution

- Pauli, one of the founders of quantum mechanics, was deeply interested in symbolic patterns and dream imagery.

- He speculated that quantum indeterminacy might point toward a deeper level of order—a pre-physical, pre-mental domain—matching Jung’s archetypal realm.

- Pauli and Jung saw complementarity: just as light can be both particle and wave, reality might have both psychic and physical aspects depending on the “mode of observation.”

4. The Core Concept

- Unus mundus = Unified order

- Psyche and matter are not causally linked in the conventional sense but are expressions of the same substrate.

- Observable in phenomena like:

- Synchronicity: meaningful coincidences bridging inner experience and external events.

- Symbolic dreams: imagery that mirrors scientific or physical realities unknown to the dreamer.

- Creative insights: scientific discoveries emerging from symbolic dream states (e.g., Pauli’s own dreams influencing his physics thinking).

5. Modern Resonance

- While unus mundus is not a scientific theory in the strict sense, it resonates with:

- Systems theory and holism in biology and physics.

- Some interpretations of quantum nonlocality (entanglement as a metaphor for interconnectedness).

- Information-based physics: reality as fundamentally informational, with mind and matter as two “formats” of the same code.

In short, Jung and Pauli’s unus mundus is a philosophical-metaphysical bridge between the subjective world of meaning and the objective world of measurement, proposing that both arise from the same deeper, unified order of reality.

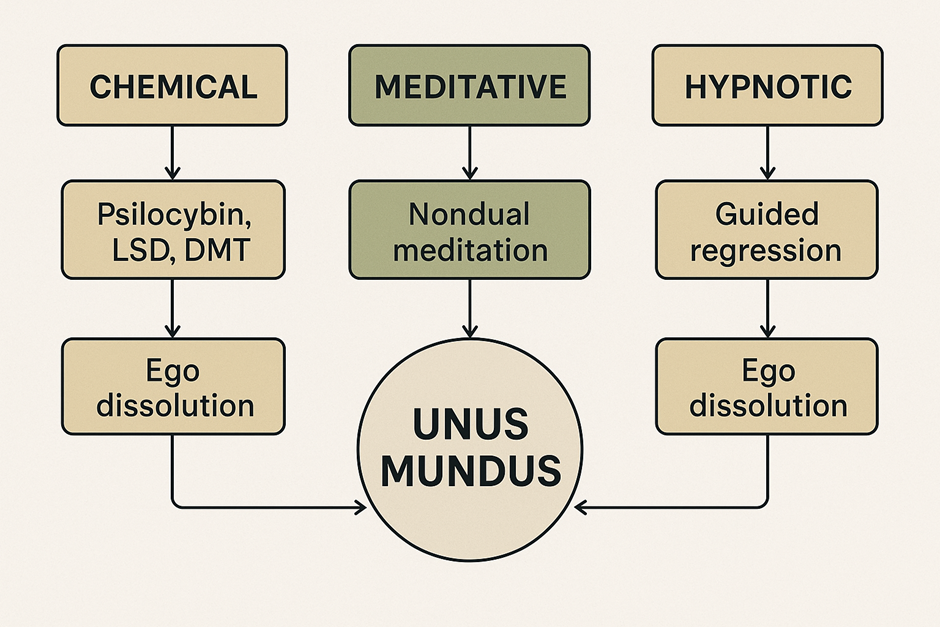

If we take unus mundus seriously as a shared underlying reality between psyche and matter, then the question becomes: how might someone alter consciousness to perceive or experience that unity?

Here’s a structured approach based on three avenues—chemical, meditative, and hypnotic—while noting that unus mundus is not a physical location but a state of awareness or mode of perception.

1. Chemical (Neurochemical Modulation)

- Psychedelic substances (e.g., psilocybin, LSD, mescaline, DMT)

- Research (Carhart-Harris et al., 2014; Griffiths et al., 2016) shows these can dissolve the brain’s “default mode network” (DMN), weakening the boundary between self and world—a phenomenological parallel to unus mundus.

- Jungian interpretation: reduced ego dominance allows deeper archetypal patterns to emerge in consciousness.

- Entheogens from indigenous traditions (e.g., ayahuasca)

- Often used in ceremonial contexts explicitly aimed at contacting a unified reality.

- Microdosing

- Anecdotally reported to enhance symbolic thinking and synchronicity sensitivity.

2. Meditative (Non-Ordinary States via Attention Training)

- Nondual meditation (Dzogchen, Advaita Vedānta, Mahāmudrā)

- Practices designed to dissolve the perceived boundary between self and environment.

- Jungian Active Imagination

- Entering a lightly altered state to engage with autonomous images and symbols as if they are real presences, bridging psyche and matter in symbolic form.

- Shamanic journeying

- Rhythmic drumming or chanting induces trance-like theta brainwave states, often experienced as accessing an “underworld” or “spirit world” that could metaphorically correspond to unus mundus.

3. Hypnotic (Trance and Directed Imagery)

- Guided regression

- Used to bypass analytical thinking and access symbolic memory layers.

- Archetypal hypnosis

- Suggestions framed in Jungian archetypal imagery to induce experiences of interconnectedness.

- Deep trance identification

- Adopting the perspective of a universal or cosmic principle, effectively dissolving the subject–object distinction.

4. Common Mechanisms Across All Methods

- Ego boundary dissolution → loosens separation between “inner” and “outer” worlds.

- Access to archetypal imagery → perceiving universal symbolic patterns.

- Altered time/space sense → the feeling of stepping into a deeper, timeless order.

- Heightened synchronicity perception → seeing meaning-laden correspondences between mind and environment.